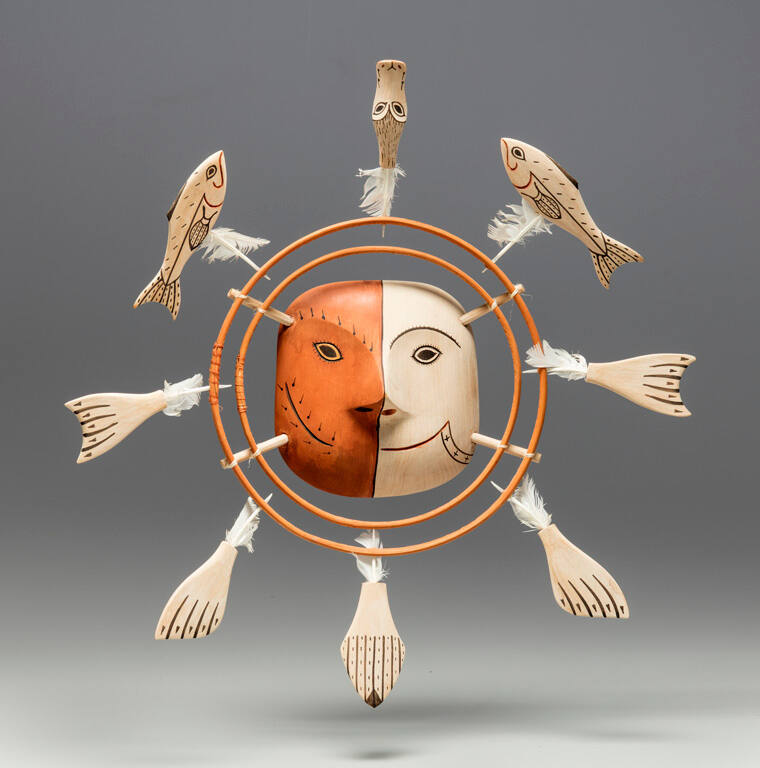

Shaman mask

Artist

Harry O. Shavings

(Inupiaq, 1909-1989)

Date20th century

MediumPolychromed wood, feathers, and raffia

Dimensions19 1/2 × 18 3/4 × 3 3/8 inches (49.5 × 47.6 × 8.6 cm)

ClassificationsDecorative Arts

Credit LineGift of Noyes Huston, Class of 1932

Terms

- Sculpture

- Polychromed wood

- Feathers

- Raffia

- Eskimo

Object number77.019.004

Label CopyBRIEF DESCRIPTION

This mask was made in the tradition of Yupik (Yup’ik) Eskimo masks worn by shaman (medicine men) during rituals and ceremonies.

WHERE WAS IT MADE?

This shaman mask was made in Alaska, where the artist Harry O. Shavings lived and worked.

HOW WAS IT MADE?

This mask was carved from wood, likely with hand tools, and painted. Notice how the artist used feathers to join the small carvings of flippers and fish to the rings circling the main face.

HOW WAS IT USED?

This twentieth century mask is similar in general form to Yupik (Yup’ik) Eskimo masks from western Alaska. These traditional masks were often worn by shamans during rituals or by dancers, who were imbued with the spirit of the mask during a performance. Such masks were often destroyed afterwards. The use of masks goes far back in time, and archaeological remains of masks have been found from the prehistoric Dorset culture.

Masked dancing traditionally took place during the long Alaskan winter in the qasgiq or communal men's house. Masks were carved, decorated and painted, ingenious theatrical devices were created and hung from the roof, and beautiful clothing was sewn, all as part of a complex spiritual life that honored the beings that made life possible in the Arctic environment. The masks were used for many ceremonial purposes; they were said to have made the unseen world visible.

WHY DOES IT LOOK LIKE THIS?

It is impossible today to know the specific meanings behind any type of Yupik (Yu’pik) style mask, as the meaning was personal to the mask's creator and related to the story he or she wished to tell. Similar looking masks could portray stories with very different meanings; elders remember many stories and dances associated with certain masks. These practices were suppressed after Christian contact in the late nineteenth century. Later, in the twentieth century, artists such as Harry O. Shavings revived the tradition of mask making, creating their own innovations steeped in the traditional designs.

Collections

Vincent Shaughnessy

20th Century