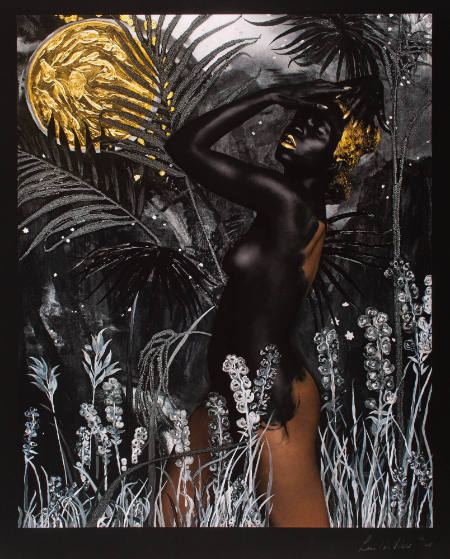

Calling Me Home, from the series As Immense as the Sky

Artist

Meryl McMaster

(Canadian, born 1988)

Date2019

MediumChromogenic print mounted on aluminum panel

Edition 3/5 + 2 AP

DimensionsImage: 40 × 60 inches (101.6 × 152.4 cm);

Frame: 41 × 61 inches (104.1 × 154.9 cm)

Frame: 41 × 61 inches (104.1 × 154.9 cm)

ClassificationsPhotographs

Credit LineAcquired through the Stephanie L. Wiles Endowment, supplemented by the Jennifer, Gale, and Ira Druker Fund

Terms

- Photographs

- Canadian

Object number2019.051

Label CopyThis work belongs to McMaster’s series As Immense as the Sky, which draws inspiration from the myths and history of the nêhiyaw (Plains Cree), part of McMaster’s cultural inheritance. As with earlier series, she plays multiple roles in realizing the final, highly cinematic tableau: photographer, performer, costumer, prop maker, and location scout.

In this work, McMaster stands at Lake Diefenbaker, Saskatchewan, as the Buffalo Child Stone. The story tells of a human infant who is lost when he falls from his parents’ sled. The child is discovered by a herd of buffalo who raise him as one of their own. In adulthood he learns that he is human, but he does not wish to choose between his human and buffalo families. Unable to occupy both worlds at once, he chooses instead to be transformed into a tremendous stone. The story resonates with McMaster, whose dual heritage—Indigenous and European—is central to her personal identity and artistic explorations.

The stone of the myth was a four hundred and forty ton glacial boulder that once stood near to where McMaster stands in the photograph. It was sacred to the nêhiyaw and a gathering site. In 1966, the stone was destroyed by the Canadian government in order to progress with the construction of the man-made Lake Diefenbaker, in spite of protests to preserve it.

In embodying this lost object, McMaster both revives it and points to its destruction, a little-known incident in the long history of colonial dispossession and cultural genocide in Canada. The artist’s eyes peek out of the mask she has created for the Buffalo Child Stone, giving it life, and a rope trails from one of her hands to the water where the actual stone is submerged in pieces, perhaps signifying a resuscitation. It draws out connections between colonization, industrial development, environmental change, and cultural loss. At the same time, it proffers a form of reclamation, or at least a way to continue to engage with a part of the earth, a sacred place, that no longer exists, through the assertion of what was lost and its creative reimagining.

—Kate Addleman-Frankel, The Gary and Ellen Davis Curator of Photography

Collections