Portrait Vessel

Dateca. 100-750 AD

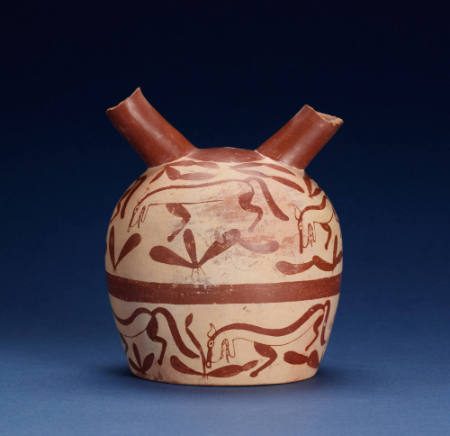

MediumRedware, polychrome

Dimensions7 1/4 x 5 x 7 7/8 inches (18.4 x 12.7 x 20 cm)

CultureMoche (Peru)

PeriodEarly Intermediate Period

ClassificationsCeramics

Credit LinePurchased by Cornell, 1882, transferred from Anthropology Department Collections

Terms

- Perú

- Ceramics

- Redware

- Polychrome

- Portraits

- Faces

- Jewelry

- Moche

Object number56.183

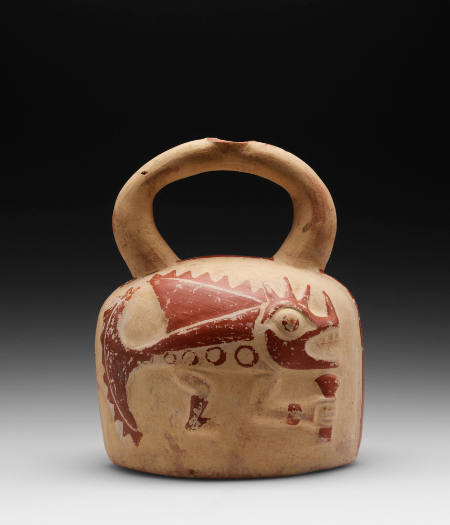

Label CopyBRIEF DESCRIPTIONThis is a Moche stirrup-spout effigy vessel in the form of a seated man.

WHERE WAS IT MADE?

This vessel was made in what is now Peru.

HOW WAS IT MADE?

The Moche made many of their ceramics using two-part press molds, a technique that enabled potters to make multiple pots of uniform design. First an original form was made from clay. After creating the mold (also ceramic) from this original, clay would be pressed into each half, and then later joined together. Sometimes hand modeling or coiling would also be utilized, and more than one technique could be used to produce a single pot.

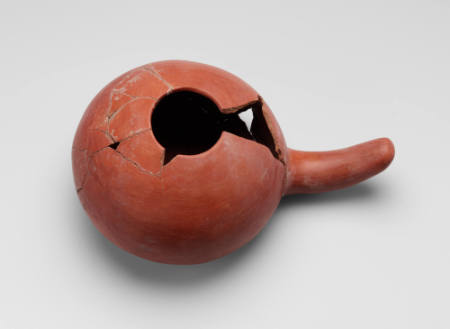

The clay used to make these vessels is known as terracotta, and the presence of iron in the clay gives it the reddish-brown hue. When the ceramics were fired in shallow earthen pits, the presence of heat and oxygen would oxidize the iron in the clay, enhancing the colors of brown, red and orange.

The combination of red and tan designs that you see on this vessel is characteristic of Moche ceramics. White clay was used to produce a paint called slip (clay diluted with water), which could then be applied to create designs. Sometimes the white slip was used to create the ground, while red slip was used to add the designs. After the slip dried, but before the clay was fired, pieces were often burnished, as this one has been.

HOW WAS IT USED?

The function of pre-Columbian ceramic vessels is not easy to ascertain. Were these vessels made for the dead, fancy grave goods with specific religious or mythical imagery, or were they treasured possessions used in life? Or both?

Although most pottery made in the past was functional ware used to cook, store, or serve foods, more elaborate pieces also conveyed social information. It appears that pre-Columbian people may have had special pots for display in their homes or for use during special occasions. According to the earliest chroniclers after the Spanish conquest, people put pottery on display in their homes that reflected what they did to make a living; for example, fishermen displayed pots with sharks in their homes, while hunters displayed pots with deer and other land animals.

Bottles of this stirrup-spout type may have been used to carry and serve liquids, since the narrow-necked bottle shape would have reduced losses from accidental spills and evaporation. Although water is vital in desert environments such as those found in many parts of the Andes, recent analyses of residues from Peruvian bottles and jars suggest that most of them were used to serve corn (maize) beer or chicha. Chicha was both an everyday beverage, made in households for family consumption, and an essential element in ritual and social interactions.

WHY DOES IT LOOK LIKE THIS?

Notice how this seated man has his arms folded across his shoulders. The large ear spools he wears are a sign of high status. Also notice the small bag or “chuspa” over his right shoulder; this type of bag was often used to hold coca leaves. Coca leaves were commonly chewed for their stimulatory effect by pre-Columbian peoples. The white-painted lines on his body probably indicate textile designs on the figure’s tunic; stripes were a common weaving motif.

ABOUT THE MOCHE CULTURE:

Arguably one of the finest technological manifestations of the pre-Columbian potter’s art, Moche ceramics have charmed generations of archaeologists and collectors with their finely executed painting and exquisite sculptural forms. Moche (formerly known as Mochica) pottery is characterized by red painting executed on a white or cream-colored slip ground. Moche stirrup-spout bottles represent a wide variety of sculptural forms, including human portraits, animal effigies, domestic scenes, or graphic human sexuality. The core area of Moche cultural influence extended from Lambayeque in the north to Nepeña in the south, and likely reflects militaristic conquest and political control by a state-level polity centered in the Moche Valley. The Moche united many coastal groups, built and controlled extensive irrigation networks, and produced ceramic vessels using molds, a technological innovation which enabled the production of vast numbers of highly detailed ceramics, including portrait head vessels so finely detailed that individual faces can be recognized. Fineline paintings depict detailed, elaborate scenes now thought to be part of the “warrior sacrifice” or “presentation theme” story central to the Moche religion. Moche metalwork also achieved remarkable levels of sophistication, with precious stones inlaid in ornaments made of copper, silver, and gold alloys.

Collections

ca. 100-750 AD

100-600 AD

ca. 100-750

ca. 100-600 AD

ca. 100-700 AD

100 AD- 600AD

ca. 100-600 AD

ca. 100-700

ca. 100-750

ca. 100-750

AD 100-700

100-600 AD