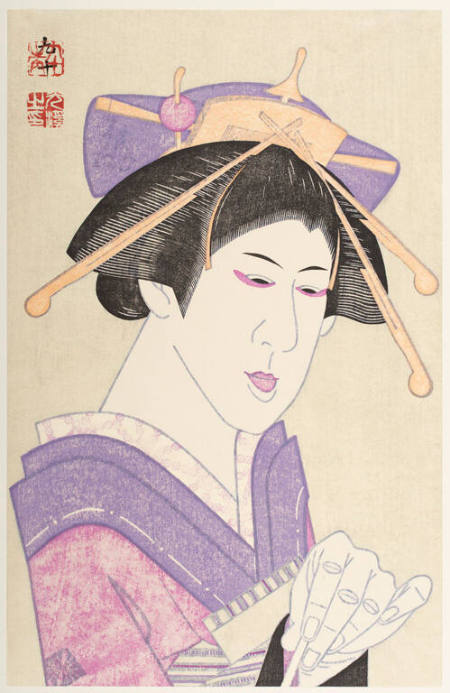

Number Two (Sono ni), from the series: The Three Landscapes

Artist

Totoya Hokkei

(Japanese, 1780–1850)

Datecommissioned for a New Year, ca. 1835

MediumColor woodblock print

Dimensions8 3/16 × 7 1/16 inches (20.8 × 17.9 cm)

ClassificationsPrints

Credit LineGift of Joanna Haab Schoff, Class of 1955

Terms

- Surimono

- Color woodblock print

- Poetry

- Landscapes

- Poets

- Women

- Japanese

Object number2011.017.015

Label CopyOeyama As the Ikuno road

Ikuno no michi no Past Mount Oeyama

To kereba Is so far away

Mada fumi mo mizu I’ve yet to tread it and see

Amanohashidate Amanohashidate

—Koshikibu no Naishi

Ori koso are Now is the time

Kasumi watarite Crossing through the mist

Murasaki no Of purple

Uenaki haru no The unparalleled spring of

Hashidate no matsu Hashidate’s pines awaits

—Omi Hino Ikenoya Mazumi

Although many kyoka on surimono use classical poems as their base, this set is highly unusual in actually incorporating the source, along with a portrait of its creator, directly into the works. The poem here, taken from the well-known anthology Hyakunin isshu (One Hundred Poets, One Verse Each), a work frequently utilized in New Year games, is appropriate to the series theme, as it mentions Amanohashidate, or the “Bridge of Heaven.” This was a long sand bar extending into Miyazu Bay in Tango Province, famous as one of the three great scenic landscapes on the Japanese islands.

According to a story about the creation of this poem, when the eleventh century poetess Koshikibu no Naishi arrived at a poetry contest, a courtier in attendance rudely asked her if she had received a note from her mother, who was just then visiting Amanohashidate, implying that Koshikibu must be getting parental help with her poetry. Without hesitation, Koshikibu proved her own merits by answering him with this verse, that includes the phrase mada fumi mo mizu, meaning both “I’ve yet either to walk there or view it,” and “I haven’t seen any letter yet.” Stories like this one lent credence to the claims of kyoka poets like Magao and others that the playful language and hidden messages of kyoka verse had an ancient history in Japan, and that contemporary comic poets were merely following in the footsteps of the exalted greats of poetry.

Collections

Totoya Hokkei

commissioned for a New Year, ca. 1832

Totoya Hokkei

commissioned for a New Year, ca. 1810s

Totoya Hokkei

commissioned for a New Year, ca. mid-1820s

Totoya Hokkei

Totoya Hokkei

Totoya Hokkei

The Waterless Shell (Minase-gai), from the series: The Poetry-Shell Matching Game of the Genroku Era

Katsushika Hokusai

commissioned for New Year 1821